- 2025-01-08

- Blog

Beyond the red serge: Mounties’ repetitive traumas and treatment needs

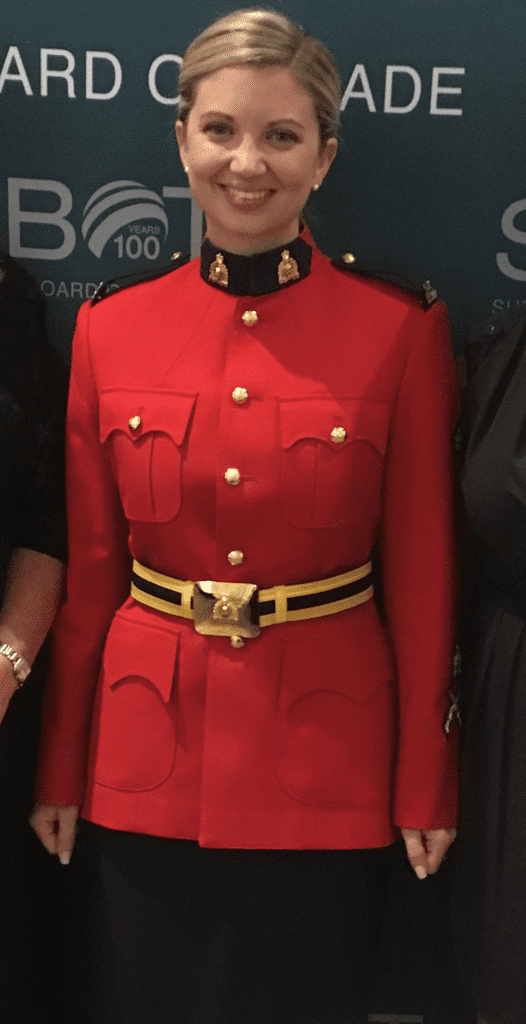

For many Canadians and others across the globe, the iconic image of the Royal Canadian Mountie in red serge and stetson is an internationally recognized national symbol, often seen at community events, citizenship ceremonies and at ports welcoming visitors from cruise ships. Lesser known to Canadians, however, are the challenges that we Mounties can face while in uniform — and what this means for our mental health and well-being, the impact it can have on our Families and its significance for the clinicians who care for us.

It’s generally assumed and understood that becoming a police officer comes with real risks to our physical safety. When we apply to join the force and begin recruit field training, these risks are expected, anticipated and regularly discussed. What is not discussed enough are the psychological risks arising from our daily exposures to traumatic events in the course of our duties. While we are issued tactical vests and sidearms to protect ourselves physically, we are not given the same tools to protect ourselves mentally.

The RCMP’s slogan is it is a “career nowhere near ordinary” and this cannot be overstated. Consider what can take place in a single front-line police shift spanning 12 hours: an officer might respond to an aggravated sexual assault, remove an abused child from the care of their parents, attend to a sudden death, and investigate a fatal head-on collision. All of these have the potential to be processed as trauma and this is just one shift of hundreds to thousands in a full policing career.

The mental health and mental health treatment needs of serving and former RCMP officers is not something that is talked about enough. One 2024 study found that RCMP officers are exposed to 13 different potentially traumatic events during their careers. That’s more than the 11 reported by other Canadian public safety personnel (PSP) and is in stark contrast to the average Canadian who will experience only two in their lifetime. This same study found that exposure to these traumatic events was often correlated with screening positive for a mental disorder, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and related research suggests that RCMP officers are twice as likely as others PSP to screen positive for PTSD.

Similarly, a 2018 study of various PSP in Canada found that 50% of RCMP respondents screened positive for a mental disorder such as anxiety or PTSD and 25% reported having suicidal ideation (thoughts of suicide) in their lifetime. When these officers were asked about experiences in the past year, nearly 10% reported having suicidal ideations and 4.1% had a plan to end their life. These past-year rates of suicidal ideation are similar to the 9.8% reported by military Veterans and significantly higher than the 2.6% rate reported by the general Canadian population.

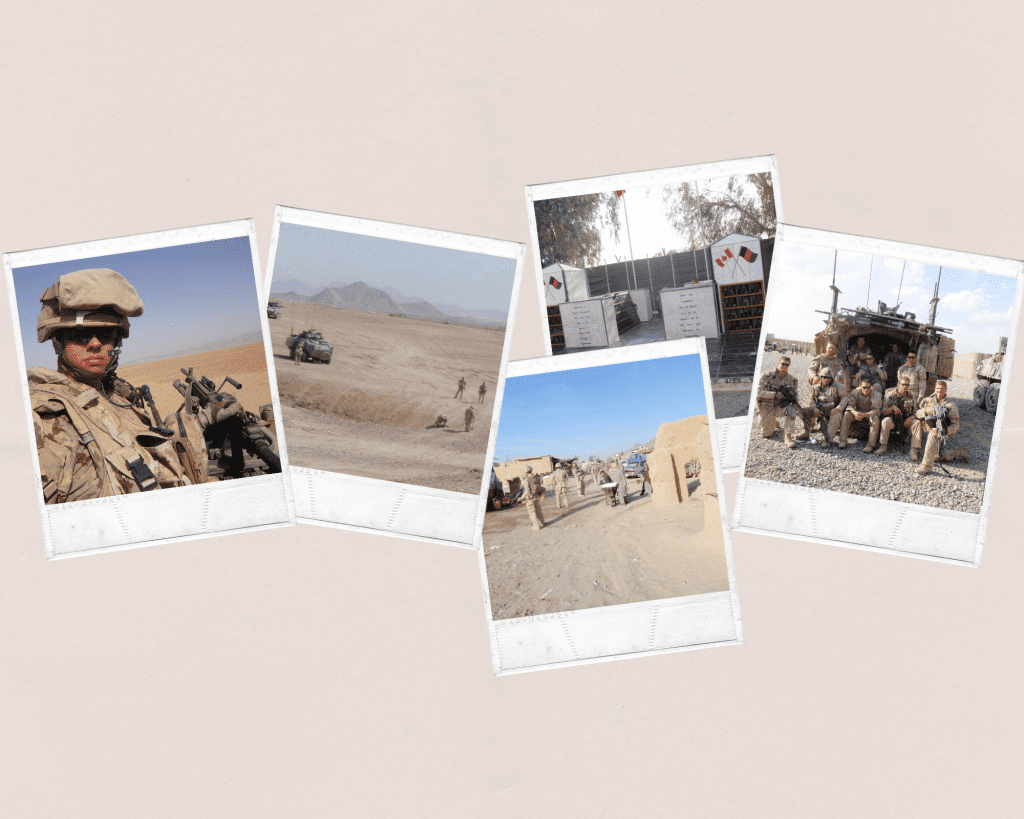

While it’s common to recognize PTSD as either a combat injury primarily impacting those on military deployments or a response to a single traumatic event, RCMP officers uniquely experience the impacts of cumulative and repetitive exposures to traumatic events. And as unique as these experiences are, so too must be the treatment designed to meet their specific needs.

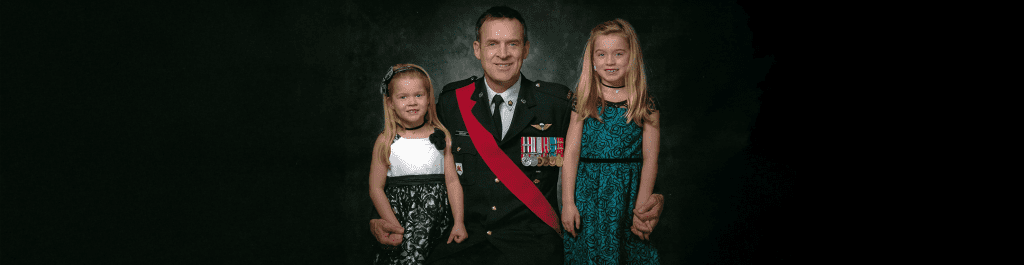

This means that clinicians treating these operational stress injuries must understand and acknowledge the realities of what RCMP officers experience as a part of their daily work and have specialized knowledge and understanding of police culture and its cumulative and compounding traumas. If we look at the field of medicine, some physicians undergo advanced training so they can specialize and treat specific populations and conditions. We see this employed by specialized military hospitals in the United States that treat soldiers who return from military deployments. In contrast, many mental health clinicians who treat RCMP officers are generalists in terms of their training and experience and lack the cultural competency and an understanding of the RCMP officer experiences. Too often in these cases, therapy sessions are transformed into educational sessions for clinicians where the client spends time filling in knowledge gaps rather than for their intended purpose. This can unnecessarily prolong or prevent recovery, create frustration throughout the therapeutic experience and create feelings of discouragement and hopelessness when ineffective treatment modalities are employed.

Further research is needed to better understand how repetitive exposure to potentially traumatic events impacts former and currently serving RCMP officers’ long-term mental health, what treatments are most effective for their compounded traumas, and training standards for clinicians who work with this population to increase their cultural competence and promote recovery and better health outcomes for this population.

— Corporal (Ret’d) Sarah Lefurgey

(With thanks to Kate Hill MacEachern for her support in drafting this blog post.)

Corporal (Ret’d) Sarah Lefurgey joined the RCMP in 2009 and was a specialized investigator of crimes against children. Sarah was promoted to the supervisor of a Major Crimes Unit before resigning in 2020. She is a member of the Women Veterans Council and the Athena Project Working Group.

Are you a Veteran or Family member with a story to tell? Get in touch with us and you may be featured on this blog!