- 2025-11-12

- Blog

Dog tags and a pair of wool socks: Stepping beyond the shadows of disability

Standing alone on the top step of Jericho Garrison in Vancouver having turned in the last of my military kit following an honourable release, I looked down at my hands — one clutching a set of worn dog tags, the other a pair of wool socks. “You may as well keep these,” said the Supply Corporal. “I can’t reissue them.”

Looking out straight ahead at the layers of the view, from 4th Avenue to the stands of tall evergreen trees in Locarno Beach Park through to the tops of the North Shore mountains displaying a gentle first snowfall, all I could think was, “What do I do now?”

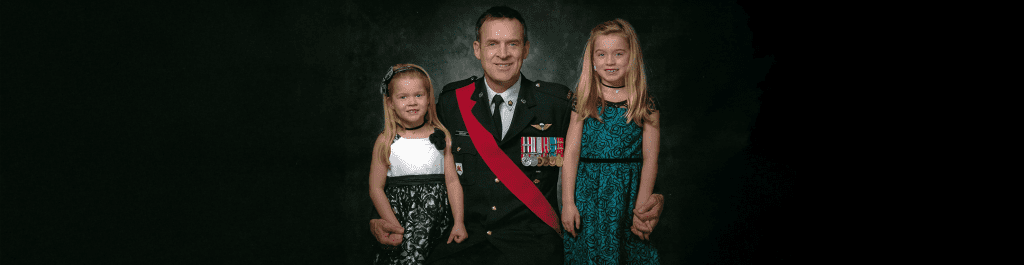

Sadly, it had come to this. After 14 years of continuous Primary Reserve service with the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), including a top candidate placing in a national training course that garnered a commendation letter from Pacific Region Commander Brigadier General P.B. Kilby, being one year out from receiving the Canadian Decoration (CD) and poised for Warrant Officer promotion, all I could hear were the Medical Officer’s comments from eight years prior when I went for a medical consultation on an injury sustained in the first year of service from combat field training: “You have two choices: I can give you a medical discharge, or you can keep your mouth shut and keep serving.” Now a has-been soldier with socks that could not even be reissued, broken physically, financially and emotionally, I felt forsaken with a bleak future.

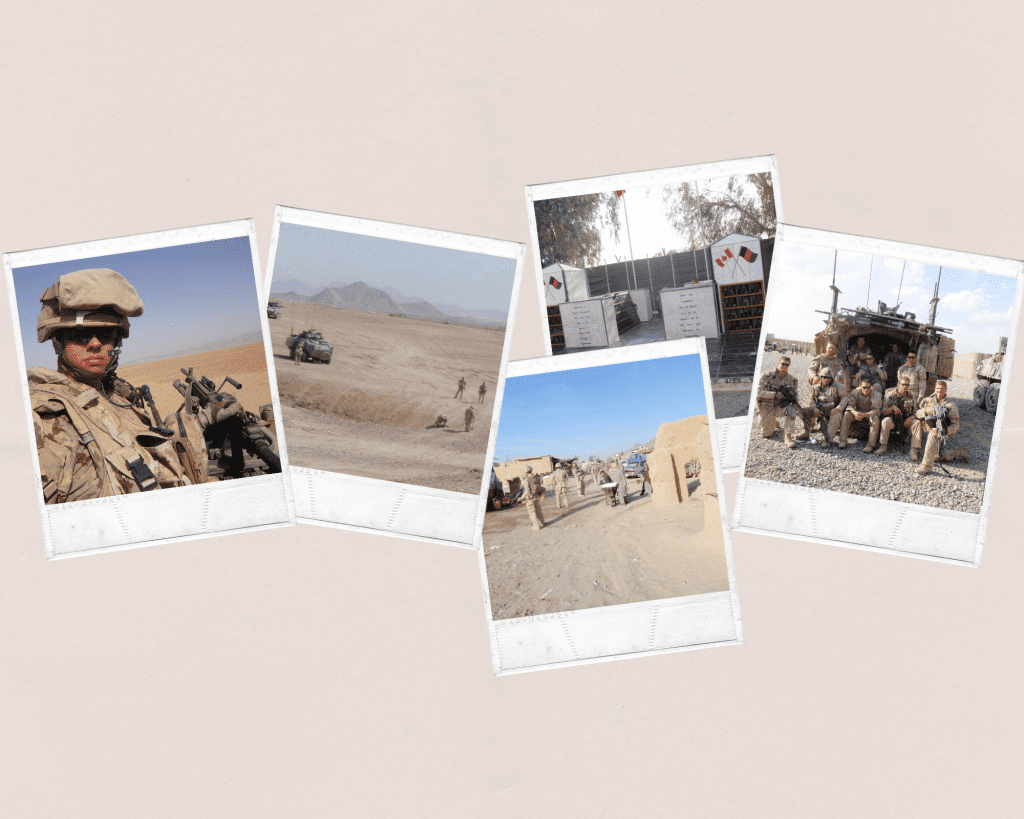

Serving in the ’80s and ’90s was not an easy time. Equipment was from the Second World War and Korean War surplus: steel helmets, 12-lb rifles, 60-lb rucksacks and reissued combat boots that were designed for one body norm. Yet there was a sense of pride in serving, wearing the Canadian flag on our shoulders and camaraderie that could only be understood by those who have worn the boots through mud, muck and mire, snow and rain that often soaked through to the wool socks for days on end.

The effects of military service were also not understood by the military, health professionals nor potential employers. “You should remove your military service from résumés,” one interviewer suggested. “It won’t make any difference to job prospects.” This statement stood in stark contrast to what a Chief Warrant Officer (CWO) on a senior non-commissioned officer (NCO) training course had once shared: “Once you put the uniform on, you are no longer part of the general public. There is a duty of care and service, and don’t ever forget this.” His words left a lifelong imprint.

Added to the struggles of post-service were the physical injuries, also not understood, particularly cumulative and consequential injuries that took years if not decades to develop. In less than a minute, the initial physical injury set the life course trajectory that would lead through valleys of permanent disability, impairment, pain, suffering and loss. Not knowing the damage being done with continued service and with no other options, I realized prior to release that I could no longer maintain the service standard I prided myself on — I was becoming a disservice and would only do more physical damage. There were no services or supports, access to medical treatments or financial assistance to reach out to at the time of release, so I was essentially on my own, navigating the civilian world without any paddles or a personal flotation device. I realized I again had two choices: sink or tread water.

To suggest the journey from service member to Veteran in the early years was straightforward, easy or positive would be greatly understated. The battle to survive at times was insurmountable. The shadows of progressing disability were undeniably the darkest times of my life, consuming and suffocating.

Throughout the past 32 years, the ups and downs have often paralleled the steepest and roughest training hills the vehicles would traverse, but the brakes on a downhill never failed, nor did the six-wheel drive — low range, slow and steady, always inching the trucks to the top. Even in the darkest days, all it takes is the smallest glimmer of light so we can step toward and move beyond the shadows of despair and disability. An eventual connection with a respected and knowledgeable Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) case manager started with one step at a time, knocking down the barriers with fairness, positivity, belief and hope. And today I am working with and supported by a wise and caring Veteran Service Agent.

The wool socks long ago worn out, the dog tags now a reminder that with perseverance, resolve and unyielding doggedness — and with the developing and advancing services and benefits from VAC and other supporting organizations, communities, stakeholders and partners — we can step beyond the shadows to well-being and quality of life.

It was the words from an Alberta rancher — in his 96th year and still driving a six-team horse plow — that resonated so deeply though it took decades to understand what he meant: “Without a past, there is no future.”

Looking back and learning from the past, evaluating and applying what is learned means recognizing the value of military service as transferrable skills, knowledge and experience, that equipment designed for only one body type can have negative impacts particularly on female physiques, that it is not possible to separate mental and physical trauma or injuries — the two are irrevocably, tightly and intrinsically intertwined. It means recognizing that the needs of Veterans and Families will be ever-evolving, and continuously learning and respecting what it takes to be a CAF soldier, Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) member or a supporting Family member.

We are then obliged to make better the days forward for those that have served, are serving and will serve — even if with one strand of trust, one step, one word, one application at a time, one new pair of wool socks. Then, one shadow at a time can fade to brightness.

— Andrea

Sergeant (Ret’d) Andrea Newton

R935 Mobile Support Equipment Operator (MSE Op), Service Battalion

Are you a Veteran or Family member with a story to tell? Get in touch with us and you may be featured on this blog!