- 2022-04-19

- Campaign

Month of the Military Child

In honour of Month of the Military Child, we celebrate the children — young and old — of military and Veteran Families. It is important to recognize sacrifices military children make, as well as their strengths, and to provide access to resources that can help when times are tougher.

Follow our Month of the Military Child posts on to this page for new profiles of military kids across Canada — those who once were and those who still are!

We hope the following resources will support your Family in good times and in bad:

- Strongest Families Institute – Military Programs: If you are looking for support with transitions such as deployments, postings, training courses, and reintegration, Strongest Families can help. Their programs help Families with children ages 3 to17 learn coping strategies on the issue of change. Services are free and available at convenient times, run by staff who are trained in military cultural competencies.

- Wounded Warriors Canada (WWC): The WWC Warrior Kids program aims to help kids to build positive relationships with peers, gain knowledge, and develop new coping skills that will help them grow and thrive.

- Guide to Working with Military Kids: This guide from Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services and Kids Help Phone offers great insights on working with and supporting military kids.

- We Have Superpowers: “We Have Superpowers” is a kids’ book celebrating the ways children of Canadian Armed Forces members and Veterans support their parents through injury or illness.

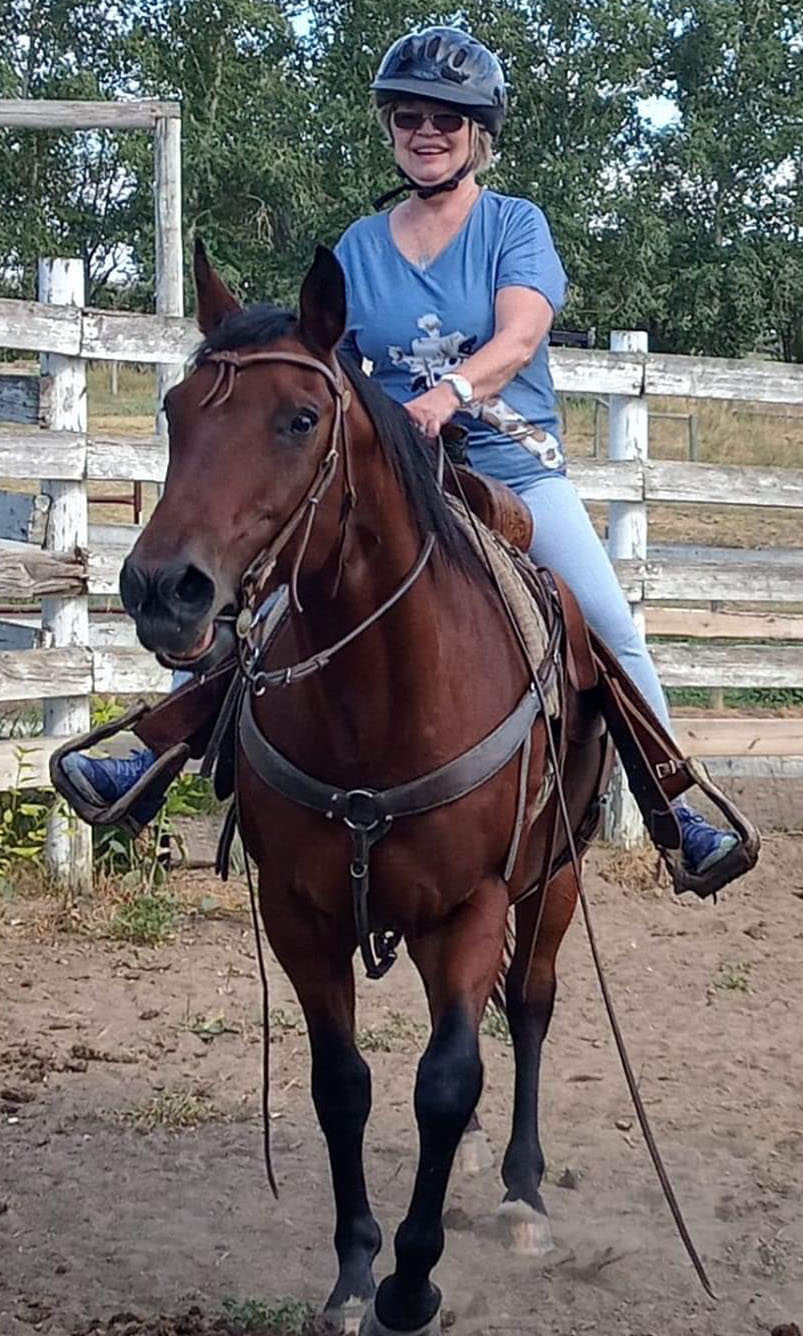

Kathryn proudly identifies as a “military brat.” Kathryn was a child in a Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) Family during the 1960s and 1970s. She lived on bases in New Brunswick, Quebec, and the former West Germany. Growing up constantly moving, leaving friends, and adapting to new cultures wasn’t always easy, but she wouldn’t change her childhood for the world.

“I think military brats either do really, really well, or they struggle. As painful as it was at times to say, ‘Why do I have to make new friends? Why do I have to start over again?’ it was the best thing to prepare me to even live in the moment. It was a great platform to learn how to be with other people beyond my own self, beyond my culture, just to explore and be curious about that,” says Kathryn.

While she embraced the opportunities that came with living in different countries, Kathryn recognizes that the transitions were hard on the whole family. It took them time to re-adjust coming back to Canada. In Kathryn’s words, “Coming back to Canada after Europe, food was bland, and we’re talking the ‘70s so we didn’t have available what we have now when we go out.”

Transitions did also weigh heavily on Kathryn’s parents. “My father was not available emotionally or even physically. He would go away, he would sign up for things that would take him away for a year. He found it really hard, after being away on an exercise, or being in Cyprus or Egypt, to come back home and fit into the daily routines of life.”

Kathryn’s mother often played the role of a single parent, running the household while her husband was away. When he’d come home, it wasn’t always the picture-perfect reunion. There was often tension and arguments that would, unfortunately, sometimes turn violent. “I remember breaking up a fight — and, of course, these aren’t the things you tell other people when you are growing up. You want to hide those things,” Kathryn says.

Healing and forgiveness

“When I left home, I didn’t know that my parents had PTSD. I was angry with them, and I felt like a swan with a broken wing. Luckily, I had my grandparents who I stayed with when I did leave home . . . I didn’t realize that my parents had PTSD until I was well into my 60s, as I started to look at my own PTSD and understand it,” Kathryn explains.

Through different therapies, self-discovery and embodying the concept of living in the moment, Kathryn has gone from resenting her parents to truly understanding them. Pursing healing and forgiveness helped her accept that we are all imperfect beings, and that it’s OK to be imperfect.

Kathryn adds, “When I look back and ask myself, ‘If I had the opportunity to live this lifetime again, would I live it the same way? Would I choose that?’ I can say, without a doubt, absolutely.”

A message for today’s military kids

“Sometimes, it’s years later that the understanding comes. That the compassion, forgiveness and acceptance of who we are and what shaped us come to light. Just know that your parents love you and are doing the best they can with what they have right now.”

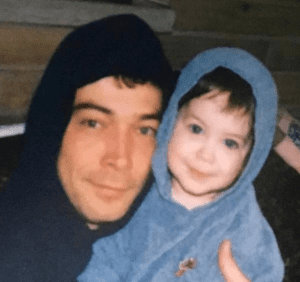

Growing up in a military Family, Grant felt that it brought a level of respect to his Family. People treated them differently because his dad was in the military. They were something special. His Family had an inspirational story, was financially set, and from the outside looking in, they had it together. But that does not mean things were always easy.

“Growing up, I didn’t really know what was different. I didn’t know what was normal. I only knew what was normal to me,” says Grant. After his father retired from the military, the adjustment was not easy. Grant found himself in a situation where he had to be hypervigilant and aware of his surroundings. He had to learn to read and relate to others’ emotions.

“I never knew what I was coming home to. I grew to be very empathetic, and in tune with my surroundings at a young age. I had to be, for my own safety. It made me wiser than I should have needed to be.” says Grant.

The isolation and lack of resources were hard. “Part of my dad’s PTSD was avoidance. My dad really separated himself from the military as he started to retire. I didn’t have much opportunity to meet other kids in my situation. So, I had to build my own community,” Grant explains.

It wasn’t until he left for university that Grant started to see what was really going on at home, that what was happening wasn’t “normal” and, unfortunately, was not okay. “I realized a lot of what I learned growing up came from living with someone whose brain was still primed for a war zone, and whose parenting skills were influenced by what was drilled into them. As a kid, the things that were expressed, and the ways they were expressed, were frightening, but I often blamed myself, because my dad never meant to hurt or scare me intentionally. He cherished (and still cherishes) me,” says Grant. “It took a long time, and multiple therapists, to hammer in that it wasn’t either of our faults, and that neither of us were bad people. That was when I started to heal, build supports, and lean on friends that I trust. The most important part of healing was learning boundaries with my parents,” he adds.

Finding community and learning to heal

“Building boundaries was hard. It’s hard to put that space in place, it’s hard to enforce distance when you know your parents need you, but I had to start taking care of myself,” Grant explains.

After setting boundaries, Grant started actively making an effort to build a community and seek help. His community started with a weekly game night and it soon became the highlight of his week. But Grant realized he needed more than one thing to look forward to. If his game night was cancelled, he needed other avenues to help him stay in a positive and safe headspace.

His newfound community helped him build back up to a place where he now feels more confident and in tune with himself. Grant has learned how to cope with difficult situations, conversations, or just hard weeks by building a large community and having different activities available that bring him joy and peace. He has learned the value of self-care through writing poetry, the arts, listening to music or podcasts, or even just taking the time to have a nice bath. Actively choosing self-care has made a big difference in his day- to-day.

“Sometimes, it could be hard to talk about the difficult things that went on. It’s hard to do that while equally expressing how massively I love my parents,” says Grant. “I was cynical about the idea of hope. I was depressed by the thought that hope wasn’t there. But with the right friends, the right medication, the right process — it’s hard to say it’s there, but I am saying its possible. It’s still a struggle, but more days are good than bad now. It is possible for things to get better,” he adds.

Anne, who grew up around Québec City in the 2000s in a Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) Family, is proud of her father and the sacrifices he made for his country. “My dad is a model of courage, strength and resilience,” she shares. Anne is very close with her father these days, even though her family experienced its fair share of challenges throughout the years.

Growing up in a military Family

Elementary school wasn’t always easy for Anne, who felt all alone at times. The only other student with a dad in the CAF had a very different childhood from hers. “His dad didn’t have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), so when he came home from assignment, everything was great,” Anne recalls. “They would do all kinds of activities together.” Anne’s father, on the other hand, received his first PTSD diagnosis when she was two. After returning from missions, he was tight‑lipped and tended to retreat into himself. Anne couldn’t understand why the two families were so different. “I was comparing myself to my friend, whose dad had the same job as mine, and wondering if I was the problem. I thought it might be all my fault.”

Anne wishes someone had explained to her what her father was going through back then. “It’s hard to understand that your parent has PTSD when you’re just a child,” she says. “l wish I knew what he was going through, what he was thinking.” Yet the professionals she turned to for support, though well‑intentioned, didn’t always understand what military Family life is like.

Because Anne’s didn’t understand her father’s PTSD, she ended up severing ties with him for a few years as a teenager, something she regrets. “I was mad at him for things that weren’t his fault. I was making connections that didn’t exist and assuming he wanted to be an absent father.” Anne’s friends were one of the main reasons that she eventually reconnected with her dad. She had a lot of trust in her friends, who helped her put things in perspective and encouraged her to write to her dad. “Without my elementary and high school friends, I might never had done that bout of soul searching. I might still be shunning him for things that weren’t his fault.” Bit by bit, father and daughter picked up the pieces of their relationship.

Pride and gratitude

“I’m happy with the relationship my father and I have built these past few years,” says Anne. The two have gotten to know each other anew, have relearned how to trust each other. Anne never would have dreamed that their relationship could be so good. “I really appreciate the connection we’ve built. We can talk about our experiences. I can open up to him, and he to me.”

Anne’s experiences will soon serve her in her career, as she is currently finishing a college degree in social service. “I want to help youth who are going through the same things I did. I think I can help other military kids build relationships like the one I have with my dad.” Anne wants to provide support that is tailored to the lives of CAF families, as there are still too few services for this community. She wants kids to feel heard and understood. “I think that my dad is proud that I’m trying to help other young people.”

Once she’s done her current program, Anne is interested in pursuing a bachelor’s and master’s degree and expanding her services to support those in the military coming home from assignment.

Message for today’s military children

More than anything, Anne wants young people to understand that they don’t need to bear the brunt of their family’s issues. “You aren’t the problem. What’s happening at home isn’t your fault.”