We don’t see what Veterans and their Families see

You can’t sugar-coat trauma

The lived experience team at Atlas and others from the Veteran and Family community have shared many personal stories here. Why did we do that? We wanted you, Veterans and Families, to hear our stories, and know that we’ve been where you are. Although our experiences may not be exactly like yours, they are likely similar enough that we get it.

We know that some of the reading may hit close to home for some, and may be difficult. We put a lot of thought into what and how to share. No nitty-gritty details necessary. But the reality is: you can’t sugar coat trauma.

If you found something that resonates, we hope it prompts you to get help, whatever that looks like: peer support, addressing substance use, checking in with your GP or finding a psychologist (more information on our website) and don’t shy away from medication as an option. But from our experience, both from the Veteran side and the Family side, we can promise you that this journey is way easier when you aren’t alone.

If you are already getting help, we encourage you to stick with it. It’s probably one of the hardest things you will ever do. But if you do the work, it will pay off. And we also ask that if you are in a good place, please pay it forward. Offer encouragement and support to others. Your actions help break the stigma.

Why did we share our experiences? Because not talking about it makes people feel like no one else understands. We want you to know that we see you and we hear you.

There’s nothing wrong with me

The words of A Canadian Armed Forces Veteran

In all fairness, if you were stuck in a place like Kandahar where there are people sworn to try and kill you, these would not be abnormal reactions. That’s how you should react in a situation like that. You know every hand can shoot, every backpack can explode, and every dog is trained to bite you. You should be on guard at all times. That’s a good mentality for threat zones. It is just really terrible to try to run your family that way. The way we are is not a disorder. There’s nothing wrong with me. There are times when I feel that I’m just not suited for home anymore.

The words of A Veteran Family member

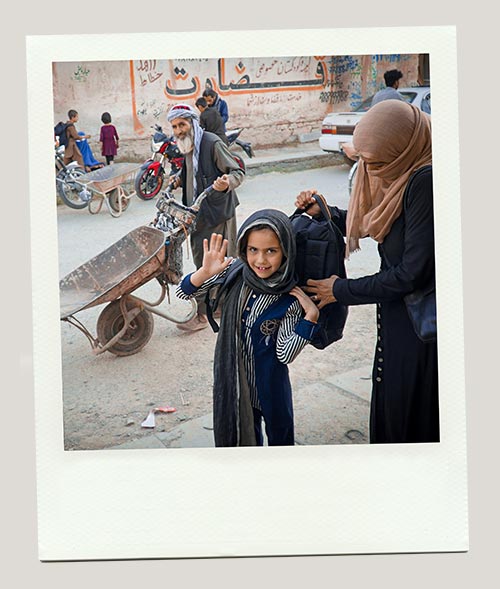

When you look at this picture, you see a happy family. What you don’t see in this picture is that my husband was just home for a visit from the psychiatric hospital.

I see you, I am you

Story written by Poliann Maher

Exhaustion…burnout…compassion fatigue. Whatever you call it, as the wife of a Canadian military Veteran living with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), I’ve felt it.

I look back on certain situations that happened in my chaotic life, when I was trying to be wife, mother, caregiver, and work full-time and truthfully, I don’t know how I did it. The only explanation I can come up with is that I was deep in survival mode. I would do anything and everything to keep my family afloat, even at the expense of myself.

There is a saying, “If you know, you know.” You know what I am talking about: those days that the shit hits the fan. You still get the kids ready for school. You get ready for work. You get out the door. You meet the day with your last ounce of energy. And no one has a clue what is going on in your life. We are very good at hiding our pain, sorrow, and the burdens that PTSD (theirs and our own) has given us.

This was my norm for several years. I’m not sure about you and your journey, but I did have one day where I decided to say “get me outta here” because the overwhelming feelings were too much. I thought there was no hope. I did it. I took the pills. And then had instant regret. This is around the time I realized how bad it was, and that the only person that could change my situation was me. No doctor, no medication, no quick fix for PTSD. The situation was not going to fix itself.

I wish I could say that once I made this realization, everything fell into place… no such luck. Unfortunately, I had acquired lots of unhealthy coping strategies along the way to keep myself going on autopilot. So, I had to learn new healthy strategies. The first of these was healthy boundaries – learning to say “no”. That was a hard one. The second one was learning what filled my cup, which was even harder. I had no idea – to tell you the truth I still struggle with this one at times. The third one was learning to communicate my needs and wants. Finally, I had to recognize I wasn’t an island.

None of these happened overnight – I am a constant work in progress. The gift I have given myself is the awareness to know what it looks like in my life when I am heading down that path of exhaustion and fatigue. Now I have a support system of my peers who let me know I am heading down that path and they encourage and walk alongside me as I get back on my wellness path.

What it looks like for me might be very different than what it looks like for you, but you owe it to yourself and your family to figure it out. You matter to so many, and you cannot help your spouse or your kids if you are depleted. So, as they say, “Put the oxygen mask on yourself first and then on others.”

I am here to tell you there is always hope, no matter how dim that hope may be. I see you, I am you. Reach out: there is a community waiting to help you navigate this PTSD world.

You’re a cop not a human

The words of An RCMP Veteran

You’re not allowed to be human. And, speaking as a human, that’s a tough one to swallow.

I’m not criticizing it, but the reality is that you’re a human being, too. Sometimes you have a bad day, but you’re never allowed to show it.

Somebody can call you every name in the book while you’re on the job, but if you tell that person to fuck off once, you’re done. There’s going to be disciplinary action. It doesn’t matter that I can’t count the number of names you called me. God forbid you call him something. If you do, he’s going to call on your boss, “Hey, he told me to fuck off. He’s got no business doing that.”

And that’s the thing – he’s right. Serving in the RCMP means you have to be something more than just human. You have to contain everything. I think that’s part of why you can get PTSD. You have to swallow so much crap, but that’s what’s expected of you to do.

You’re not allowed to be human. And speaking as a human, that’s a tough one to swallow.

The words of A Canadian Armed Forces member

Why Picnics Suck

The words of A Canadian Armed Forces Veteran

Picnics should be fun. A nice outdoor space where friends and families get together with their kids. But they can be chaotic. I think for a lot of us—for me specifically—things that are fun and chaotic are just chaotic. It’s very hard to focus on the happy that’s going on.

A kid’s birthday party is, in most circumstances, a fun and enjoyable thing to be around. But I hate them. I don’t want to go. I don’t want to host one. It’s like walking into a swarm of bees.

You know the excitement of 10–20 kids and the way their voices get? They start yelling on top of each other to get heard. The next thing you know it sounds like kids screaming. That’s the opposite of what I want to be around. That’s the stuff I’m trying to forget.

A lot of people think it’s the balloons popping that trigger some sort of flashback. I mean, it can be that. But really, it’s the noise. It’s the unpredictability. It’s someone coming up behind you and pulling on your pant legs. These things are fun for most people, but they’re the opposite of what I want.

We have drills in the military on how to manage chaos. You break it down into specific areas to watch. But when you’re alone in the situation, you get into this frame of mind that you have to watch everything, know everything, and sense everything.

You don’t.

I mean, it’s a kids’ party. It’s a barbecue in your backyard that YOU organized. It’s a picnic in a park. These aren’t stressful things, but that isn’t the point. The point is: what’s my body doing right now? My mind may say, “this is a kids party”, but every other aspect of my body is responding to noise, to threats, to chaos, and to a lack of control. That complicates the hell out of things that otherwise ought to be fun.

The radio was on 24/7

The words of A Royal Canadian Navy Veteran

We had the radio on 24/7, so people sat there monitoring the radio 24/7. We’re all listening to people pleading for help 24/7. It’s steady. You can see these people in Misrata from where you’re sat on the bridge. We could feel the crunches of the city being shelled from the ops room. We were that close. We all felt powerless. There was nothing to do. We were just exposed to this atrocity.

We briefed as a team every night. What happened that day, or what Intelligence was saying—all that stuff got put into the brief, so everyone was aware of our tactical and operational situations. So you’re aware that there’s tens of thousands of people a couple miles away from you trying to escape. Instead, they’re getting shelled.

You sit there. Listening to them plead for help on that fucking radio.

A boat needed to get into the harbour and it couldn’t because the port was mined. We couldn’t let the boat in until we cleared the mines. The whole time we were trying to clear the mines, they were constantly asking if they could come in, when they could come in. You know that your mission is to clear this mine. You have that mission because the mines were erupting, which impeded people from escaping. We know there’s processes to follow. The work we do is to clear those routes for the sake of the ships. But our work taking one more day meant one more day those people were exposed to that situation, and that was horrendous.

You normalize it

The words of A Canadian Armed Forces Veteran

I got called by the Special Investigation Unit in the military. I had been out of the military for about three years at that point. I was called in for an interview about another woman who had been sexually and physically harassed. I was in the interview room with the police officer for three hours. The officer who was recording asked me, “Did anything ever happen to you?”

I said, “No.”

“Well, your body is telling me something else,” he said. “We’re here if you need to talk.”

I couldn’t understand. After I left, I was very, very angry. It was like I had gone back ten steps. I was pissed off. I couldn’t even explain how I was feeling.

Then the stuff started coming out. Friends of mine reached out and told me they were in the class action. A good friend told me, “You need to start talking about what happened to you. You cannot let it go.”

So I did. I put it all down on paper, and sent it off.

What people don’t understand is that you’re dealing with so much shit as it is in the military. You have to normalize it to be able to move forward, or else you’ll be stuck there. So you bury it, and you tell yourself it was bound to happen.

You question yourself. Any person violated by a sex crime will tell you that. They’ll question everything. Was my skirt too short? Was my top too low? You blame yourself for it.

You cling to a sense of belonging. You want to belong somewhere, so you suck it up. You suck it up and you say, “Hey, you know what? I have a job, I have great benefits.” You normalize it.

The words of Bill “Mother” Irving Chief Warrant Officer (Ret’d)

I just recently started trauma therapy. It’s been sixteen years since the last time I saw a therapist. It’s very difficult to relive those moments as part of the rehab: the details required to help me get through it, to help me at some point accept it and be able to deal with it better than I have been for the last number of years.

I was in therapy after deployment back in 2006 for about six, eight months. I got my diagnosis then and I stopped seeing the amazing mental health person I was seeing back in in ‘06-07. Typical of most people in uniform, I managed to deploy after the diagnosis three, maybe four more times. And it just became cumulative. And then I hit the wall, hard this past summer, for a number of different reasons. Stuff was coming apart a little bit inside. My love of alcohol was moving to the forefront, and I was starting to let my priorities slip. I hit the wall, for sure, and I reached out for help. Help was instantaneous.

I got back into treatment both physically and mentally now. It sucks. But it is what it is, and I’m committed to it. We’ll see where it goes. There’s days where I come home and I physically will stare at a bottle of Jack [Daniels] for what feels like hours. And I want to throw the cap off. But I can’t. I recently made the decision to focus on my rehab, deal with my substance abuse issues, and get my head spacing and timing right for me – and for everyone else in my life.

It’s so funny that I talk openly about mental health. And yet I guess for me it’s hard to internalize it. Some of the positives is the realization that I gotta take my foot off the gas with some stuff; I’ve got to focus better on other things. And just be me. It’s okay to just to be me with my issues, and make sure everyone knows, “Hey, Bill’s off today, and there’s probably a reason why he’s off. So just cut him some slack.” It’s just all communication, prioritizing, and getting to where I need to be for me.

Part of the reason why I went ask for help was that the kids had to use the safe word – which is a dumb term, I’m not a cliché guy. But, we have a word that if I was becoming rage-y dad, as we laugh about sometimes, they would just throw this word into the conversation and I hope to catch it. And then I just take myself out of that situation at home. My wife hears it all the time. I am tough to communicate with about it. I am trying to get better. It’s all part of the process. But it’s hard. It’s 30-year career: you just can’t make changes. It’s a marathon, not a sprint.

My career [is something] I have zero regrets about. It made me the man that I am today, the father that I am today – though I can be a handful – [it made me the] brother, friend, etc. But, my career was spectacular. I joined the military to do things. Man, I did them. I stand tall on that for sure. Your career defines you, but you define your career.

So you know, stick your chest out, hold your head up high and enjoy the career. It sucks to hear people getting out on negative terms, understanding their circumstances, man, but at the end of the day, it’s a dangerous job. It’s a tough job. It affects you, and if it doesn’t, then you’re some kind of robot, dude. You want to ask the question about my career ask me the question, because it shows me that you are interested in what I’ve done and perhaps how it’s affected me, if that makes sense. I think my appearance sometimes doesn’t help me, right? But just ask the question. I think most Veterans that I know, that I’ve served with, have little catchphrase, “Those that have done, usually don’t talk about it.” Right? So, we will [speak about it] if we’re asked generally, and we’ll give you general terms. We’ll talk about it. You asked me, and I’ll engage with you. And if something becomes too tough, then I’ll say, you know, I’ll put up boundaries and say “I can’t talk about it” or, “I don’t want to at this moment.” But just ask.

Like I said, I recently started [dealing with] the trauma side. I wasn’t prepared for it. I thought I was, but it sucked. Part of my homework was to walk through a Walmart, or Costco, or the shopping mall or just drive through downtown Kingston for one hour a day. But then I [also] had to listen to the recording of me explaining one of the most serious, serious incidents that affected me for my [whole] career. I couldn’t not listen to that recording all last week. I barely did my homework, and I almost canceled my appointment yesterday. Because I was that messed up from last week. But again, I committed to it. I need to do it. And I will do it. Just walking through a Walmart with the crowds, the noise. It just seems very chaotic to me. Even Costco – it’s just always crowds, the noise, the threat. There’s always a threat and it’s so stupid. But that’s every day. Or you’re always eyeballing somebody. Whoever walks past you, you’re like, where’s the threat? Where’s my exit? Where’s my support? Where’s my weapon? Where’s my radio? It’s always. It’s a constant. And I haven’t deployed since the Philippines in 2013. How long ago was that? That’s almost 10 years ago, but my mind always takes me to that deployment or one of my earlier ones. it’s always there.

So it’s just learning to go to the Walmart and say, “I’m in Walmart, man. It’s all good.” It’s getting to that. I haven’t done an hour yet. I think I’ve maxed out at about 12 minutes. And then I’m like, “I’m out of here.” My doc, she’s good. She’ll hold my feet to the fire. It’s like doing a few rounds with Tyson. But it’s all good. I’ll get there, I’m sure. My kids get a charge out of driving with me. Because I get pretty vocal and stuff. And they’re just laughing like, “Dad, what’s going on?” And I’m like, “well, I’ll tell you what’s going on.” Stuff like that, you know? It’s really just crowds, quick movements and noise. It’s all that stuff. It’s everything you’ve heard a lot of Veterans say, I’m sure.

It’s weird, man. Because you know you’re home. You know you’re in Canada, or Kingston or wherever the hell you are. It’s just hard to process it quickly. I guess hypervigilance to me is just that alert state. Right? There’s the moment you cross the LD – the line of departure – whatever time your mission starts, man, you better be on it. All the distractions from camp, that last terrible phone call home or good phone call home, whatever the hell’s going on. You need to separate yourself from that and get into the mission. Get into the mission. And so that’s hypervigilance for me. You’re cutting off everything else, but you’re so focused on the task.

Why do I go to my neighborhood pub? Because I love it. But why do I do three drive-bys of it [before I go] to make sure I know the cars that are in the parking lot? It makes no sense to me. Something as simple as that is hard for other people, I think, to understand. Even going through the door. Everyone knows me knows that when we go out I gotta sit in a certain spot. And when I’m out with my wife, she knows I gotta have the aisle or look out. You know, I get up, walk around, I gotta check everything out. So your senses are so in tune, but it’s also so tiring. Because now when you come home, you’re coming down off of that, just like you would post-mission. Normally for me anyway, that would be my pattern, right? The adrenaline rush throughout the mission, and even lulls within it. An incident happened, sure, everything’s heightened.

That’s what hypervigilance is to me, still. That’s why this trauma therapy is tough, because you’re in back in the moment and you’re in it for an hour and a half which doesn’t seem like a lot but it’s flash to bang. And then you come out and you’re just the spent casing. I’ll start with my wife, I just have a hard time communicating to her why I’m off, or if off today, or if I need some space today. I just generally don’t [communicate] sometimes, most of the time – probably all the time. I can cause friction for sure. She knows me well enough that she’ll say “go for a ride.” “Go to the garage do something.” It’s a friction point, for sure. It is learning how to communicate it properly. That’s a two-way street.

And for the kids, I mean, I want to be the best dad I can be but sometimes I can’t be and they know that. We’ve talked now that they’re older about why I am the way I am sometimes. They know too, now. I fear early on that they didn’t know why I was so mad, or why I was the way I was. But now they get it. We’ve incorporated this [safe] word, if need be.

My young son wrote a poem. It was about life in the trenches. It was about World War One. It was a very cool, it was very well written. And he said in there, “I wonder what it would be like to be back then. I wonder what it would be like to be my dad.” So, if you read this, from a 12-year-old, you’re like, man, what? What have I done or shown him not talking to him about it, which I wouldn’t do earlier. But now, I’ve changed and I’m a little more open with them about my mental health and my physical ailments from my career. “Dad, you want to play catch?” “I’m super sore, buddy.” Now they kinda understand that, whereas before, I’m not sure that they thought I was engaging properly as a father. I don’t know. It’s an evolution.

I love an adventure. I want to just do stuff and have fun doing it. I’m a very social person. You know, riding with my brothers. Just doing crazy stuff, man. We’re heading to Myrtle Beach. I have to learn how to kite board. I’ll probably pull every muscle in my body, but I’m fucking doing it. Life’s too short, stupid cliché, but it is. I’m lucky to be lucky to be alive. 100% So let’s enjoy it. And that’s the give and take with me and my family: I get a lot of slack to go do that to clear my head andthen come back. Normal dad, normal husband, normal friend, normal brother.

I’m a proud Veteran. No regrets. No regrets of my career, like I said, and I served with some warriors, men and women, in some very tough places in this planet, but proud Veteran and I’m proud of all the men and women that I served with.

Hypervigilance is all I have

The words of An RCMP Veteran

Imagine you’re sitting somewhere on a nice, sunny day with your family. Everyone is taking in the day, except for you. You’re constantly looking around, looking at people’s hands, and not paying attention to the conversation.

This doesn’t bode well for family members. Even your children will say, “Oh, Dad’s pretty wound up today.” If you’re driving, you’re doing running commentary the whole time, “Oh, look at this guy running through a stop sign.” “Oh, look at this guy, he’s driving like an idiot. He’s on his cell phone.” My family is just like, “No, just drive.” That’s really what they say to you, “Just drive. For Christ’s sake, just drive.”

But that’s the thing. You go into the RCMP, and you’re absolutely going to come home an overprotective parent. You are. You’re not doing it to harm them—you’re doing it because you’ve seen a million bad things happen to children. You lived that. Now you have to pick up the pieces.

If your kids tell you, “I was invited for a sleepover,” you launch into full operational mode. “Okay, I need a full background check and credit check on the parents to make sure they’re okay.” If you let them go to the sleepover, you’re putting them in harm’s way. If you have a sleepover at your house, they think you’re an asshole, because you’re checking on their safety by barging into their room every 20 minutes. That’s how my mind manages life now. I can’t stop it. And I don’t know that I want to stop it. Hypervigilance is all I have.

The words of An RCMP Veteran Family member

Smells like deployment

The words of A Canadian Armed Forces Veteran

We have some land, and we have one of those shelters to store our tractor in during certain parts of the year. I can’t go into that shelter. If I get close to it, I’ll look at my husband and tell him, “I can’t do it. It smells like deployment.”

Smell has always been a big trigger. It still is. I think it is for most Veterans.

I don’t know if it’s because the shelter smells like a mixture of rubber and diesel. That smell is an instant panic attack.

I’m getting better at dealing with it, because now I have tools to do it. But every time that scent hits me, I’ll know the panic is coming. “Here we go. We’re back in Haiti.”

To calm down, I have to physically move away. I go for a walk. I take deep breaths. I try to control it. I face it. I will still go and take little steps. I’ll open the door and take deep breaths. I tell myself, “This is not Haiti. It smells like Haiti, but this is not that area. This is your backyard. You’re at home in Ontario.”

That’s how I’m able to cope with it. It’s been 12 years, but I still have triggers like that.

You and I could be walking down the street and see the exact same thing, but we won’t react in the same way. I can react instantly, and you react two years later. When you’re in the action, you smell it, live it, feel it. It’s in your skin, it’s in the sun—all of your senses are affected.

If you don’t want to see something when you’re at home, you turn off your TV. When you’re in the action, you can’t turn off the TV. You can’t make it stop. You cannot unsee when or what you saw, felt or smelled. It’s there. It’s still there. It’s in you.

The civilian world does not get that.

I always worry

The words of An RCMP Veteran Family member

My friends always ask if I worry when my husband goes to work. The truth is, I can’t. You have to be able to compartmentalize. As much as I know that some calls aren’t dangerous, I also know that at any given moment, there could be a guy who decides, “Hey, today is the day I’m going to take out a cop.” You stop someone to give a traffic ticket, and that could be it. It could be over. You never know.

Man, you have to let go. All you can do is pray to God that he comes home at the end of the night. That’s the biggest thing. You cling to the hope that he will come home at the end of his shift.

Where do I stand?

The words of An RCMP Veteran Family member

Jim loved his job. He absolutely loved it, despite what he dealt with. Sometimes the job takes precedence. “Wait a minute,” you say to yourself, “that’s not right.” But you know that they have to go. They get called, they go, and you ask, “What about me?” You’re sitting at the kitchen table, alone. They go off and do whatever it is they’re going to do.

It’s not that you’re not number one. It’s just that they deal with a lot of responsibilities, and some of them conflict. That’s the reality of loving who you love. They have a heart that cares about a lot more than just you and your little world, and that’s a good thing for society. But it’s brutal on a relationship.

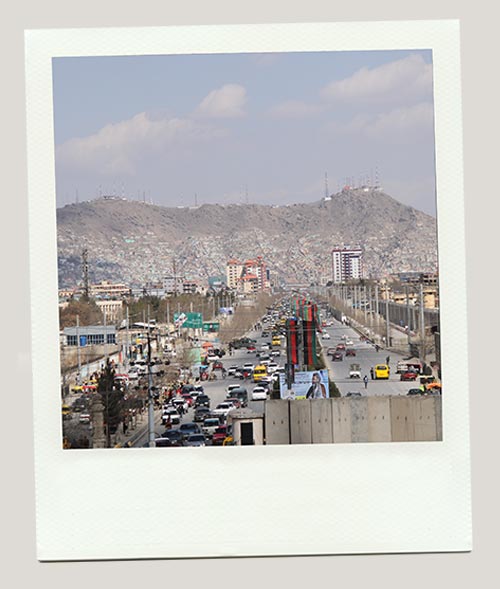

Afghanistan is his mistress

Story written by Laryssa Lamrock

I’ve always said that if I was going to write a book I’d call it “Afghanistan Is His Mistress.” If you are the family member of a Veteran living with PTSD, you’ll understand my title.

Trauma can grow from many different experiences, places, or events. You can modify the title whatever way resonates with you, but for me, it’s Afghanistan.

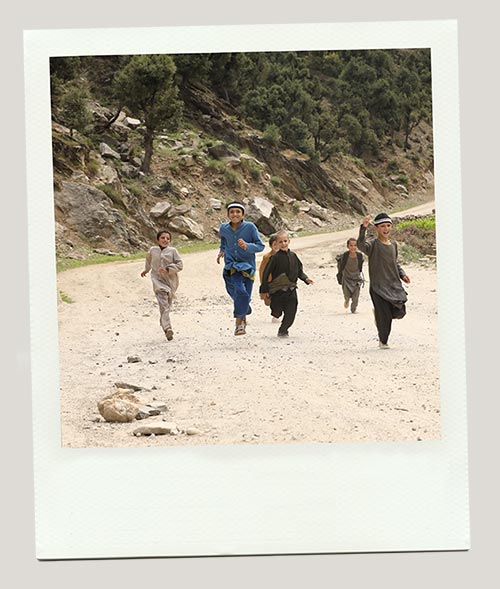

My spouse did two tours in Afghanistan. We weren’t a couple at the time, but I know this for sure: part of him is still there. Still with Afghanistan. The country, the people, the time spent together. Her beautiful children. (Oh, how he loves Her children.) His thoughts are often lost, recalling times past that are still vividly present. He is compelled to movies, news and social media posts about Her. And I know he dreams of Her.

It’s a part of him I’ll never know or have access to. It belongs to Her.

There is some of his history with Her he’ll discuss. I know many of his experiences, both the good and the not so good. But some he won’t discuss. It’s their private story. One I don’t have a right to and I respect that. And I likely won’t ever truly understand his connection to the country where he dutifully served and left part of himself.

Trauma is so deeply personal and private. It has been a challenge for me to learn that, although my husband and I are best friends and we rely on each other, there are things about his trauma he doesn’t want to share. And for whatever his reasons are, that’s okay.

Our loved ones keeping some things private isn’t a reflection of their love or trust in us. It doesn’t speak to the strength, depth or quality of the relationship. More important than listening to full disclosure of things we might later realize we didn’t really want to hear is that we are available. Without judgement or pressure or expectation of our loved ones and what they choose to tell us. Chances are they often impose that judgement, pressure and expectation on themselves, even though we may not see it.

So, although Afghanistan may be his mistress, I know I am something much more than that to him. I am one source of his support, his sounding board, bullshit detector, partner and ally.

And the ironic thing is, some of those things have been Her gift to us.

This is in B.C., not Kabul

The words of A Canadian Armed Forces Veteran

The more I can connect with the room I’m in, the circumstance I’m in, the reality of here, safe in Canada, the less I am suffering.

One of the ways I get out of that is to remind myself of the colours I am actually seeing, like right now in my study.

I’m seeing blue: my backup screen on my computer is blue. My wife left her phone in the room, and it has a blue case with white flowers on it. I’m seeing yellow: my kid made me a coaster with a yellow smiley face on it.

Those are just colours, but they draw my body and mind back to the fact that I’m in B.C. This is not happening in Kabul. This is in B.C. Then you go from things you can see around you to three things you can hear. You get yourself to actually listen to the sound of your bird chirping, and your furnace humming in the background.

The more I can connect with the room I’m in, the circumstance I’m in, the reality of here, safe in Canada, the less I am suffering.

It’s never too late to reclaim your culture

The words of An Indigenous Canadian Armed Forces Veteran

“I almost died shortly after my career ended. I have IBS (irritable bowel syndrome) because of trauma, including military sexual trauma. My body started to break down and my digestive system stopped working. I was probably a week away from going septic.

“What saved my life was one of my Elders: Grandfather Joe. He said: ‘Come and talk to me. We need to talk.’ At first, I told him nothing was wrong. Eventually, I told him all of it.

“He said: ‘You’re sick and you’re only going to get sicker if you don’t do this: Find a birch bark and write your story on it. Then take the bark and all the documents, put them in a fire with some tobacco and cedar, then walk away and don’t look back.

“I did everything he told me to do. Within 24 hours of completing that task, my guts unlocked and my doctor referred me to a specialist.

The ceremony literally saved my life.”

The words of A Canadian Armed Forces Veteran

“Thank you for your service”

The words of A Canadian Armed Forces Veteran

What happens to soldiers a lot is that you start to accept the things you can’t control. Which makes you obsessive about the things you can control.

If we’re going to speak about the times that weren’t fun—the really tough times—I want people to remember who got them their freedom. Some people in this country are so incredibly free that they forgot somebody gave them that freedom.

Don’t credit me for that. Go on Remembrance Day and hang out by a cenotaph for like 30 seconds of honest reflection. That’s way more important. I got to live, I don’t need to hear thanks. I would feel better if they understood who gave them that freedom: those who died for it. That would mean more to me than “Thank you for your service.” Like, okay. Cool. But I get to live.

There is a randomness to conflict that I think a lot of people may not understand. What does it mean to die at 22 when you’re just in the wrong place? You can have all the tactics and equipment in the world, but when they produce a bomb that is so big that your armour is no match for it, there is nothing you can do. The lack of ability to influence things like that is a really tough thought to process. What happens to soldiers a lot is that you start to accept the things you can’t control, which makes you become obsessive about the things you can control.

Back here, you call that person a control freak. That way of being doesn’t match up with life in Canada. In Canada, that person is obsessive. To me, that’s just how I function. In the military, I knew everything there was to know about the things I could control in any given situation. I could put my mind on those things. If I sat back and let those things slide, and started stewing about the things I couldn’t influence, I’d be fucked. You still gotta drive down that road anyhow. You’re still going. What would you rather do?

My survival mechanism was to 100% master the things that I can control. That’s not a great way to run a family, but it is a good way to plan a patrol. It’s a very good way to plan a patrol. If you gotta link up with a helicopter, I recommend this strategy. If you gotta plan a holiday with your wife, I don’t recommend it. But try and get someone who survived thanks to these strategies to just drop them. “I know it kept you alive, but just don’t do it anymore.” What are they going to say? It’s not that easy.

A note on the dining table

The words of A Royal Canadian Navy Veteran

When we deployed, it was 22 hours from the time I was told that we were going until the time we sailed out of Halifax harbor. You don’t know how long you’ll be gone. My wife wasn’t even home when I got the news. She was away. It was terrible weather. March 2 was the day we sailed out. My wife had a friend drive her from Cape Breton to Halifax. We saw each other for an hour the night before I sailed for six months, to go into what Libya became.

A few people had to leave notes on their dining tables to say goodbye, because their families weren’t home in the 22 hours from being told to being gone. They didn’t have a chance to say goodbye.

And some of them never came home.

I chose this life

The words of An RCMP Veteran

I spoke with someone who said, “Because you were never told about all the things you might face, you’re like a victim. You’ve been victimized.” I told her, “Never, ever use that word with me.” You know why? Because it was my choice to serve.

It’s true that I joined with a certain naivety. I didn’t know all the side effects that were waiting for me at the end of the tunnel. But no matter how bad things were, or how messed up I got, I’m still very proud of what I did.

I am not a victim.

It says Ukraine, but it could say Sarajevo

The words of A Canadian Armed Forces Veteran

Some weeks are harder than others for me. Some of the things that that trigger me are current events. I think for a lot of us, the news says Ukraine but it could say Sarajevo. They’re very, very similar. Ukraine will create a lot of the same issues. You’re going to see cold, starving, old people soon.

That’s my weak spot. A lot of people’s weak spot is kids. For me, it’s suffering, old people. For whatever reason, it’s harder for me to watch. I know that’s coming.

I may not know exactly, but I have a pretty good idea of what that town of Kyiv is about to go through. I don’t need to watch a single newscast to know that. I know what urban fighting does. I know what culturally motivated urban fighting does. It’s awful. I get in my mind thinking of those things.

Watching these conscripted soldiers has been tough. I can look at the stuff Canada’s asked me to do, and I can still, hand on heart, say I believe that those are the right things to do. If I felt they were wrong, and I didn’t want to be there—Man, that would suck. That would be awful. When I watch this 20-year-old kid who didn’t even know he was invading Ukraine until the day he’s invading Ukraine, that’s brutal. It’s hard enough when you agree and believe in what you’re doing, and you want to be there.

Nowhere in basic training did it tell me I would be—or did I agree to—watching old people go hungry. Kids losing their right to just be kids. That loss of innocence. Nowhere did it say that I might face an armed opponent who’s coerced to be there, who doesn’t even know what he’s doing. It’s a horrid situation and it’s going to trouble a lot of Veterans and Families who lived through the Balkans.

Being a friend

The words of A Canadian Armed Forces Veteran

It’s really hard to be friends with people like us, especially if that person isn’t one of us. It’s not because we’re vetting them, or we’re rude, or anything like that. It’s that friends of mine have to have a high tolerance for me bailing. I bail all the time. I cancel stuff and I say no more than I ought to. So much of that is because I said yes one day, and then today is not a good day. It’s so much easier to say yes when it’s another person who’s probably looking at the situation in the exact same way I am. You can be yourself in that situation. There’s less judgment. If I were to react to a noise, those guys would either ignore it, ‘cause they get it, or they’d laugh if off because hey, they’ve been there.

I’d probably take it a little personally if I saw someone laughing at me for that. But I have way more tolerance for being bothered by people that I have served with than by people I haven’t. It’s a different layer of acceptability. It’s probably called discrimination in anyone else’s conversation, but that’s kind of the truth of it. One of the reasons I’ll go to the house of my friend who I served with is that if I have a reaction there, I know it’ll probably blend in with the reactions they’re used to seeing from the other people who come by. It probably won’t be off-putting to them if I walk in and 10 minutes later say “I gotta leave.” I don’t need to come up with a bullshit answer for them as to why. They all know, and they’ll invite me again because they get it. But it becomes very difficult to be friends with someone like that when you don’t get it. It seems like we’re bailing on you.

This is where my family has helped. We’ve developed strategies so that if I have to leave 10 minutes into a family function, we’re not packing up the kids, disappointing them and everyone else with little explanation of why we’re out. Often we’ll take two cars, so if I have to go, my wife and kids will stay. Or my wife will leave the kids with her family and drive me home quick before she heads back. It makes us feel like we’re in this together, that we’re tackling the issues from my PTSD—those issues that affect her just as well as me—as a couple. And we’re doing it in a way that calms my nerves about the whole situation. Having a game plan is critical.

Vicarious trauma

The words of A Veteran family member

I know more and have seen more than I ever want to see in my life.

“You can’t hang out with that kid and you can’t go there and you can’t do this and you can’t do that,” his dad would say. My son would ask why not. “Because I know things that you don’t know.” My children loved their father like nobody’s business, but the eldest one moved out of the house when he was 20. It’s not until after his dad died that he said to me, “I had to move out. I love dad. But I couldn’t live with him anymore.”

He couldn’t deal with it any longer, so he had to move out. That’s why we always say if one person has PTSD, the family has PTSD. That’s my perspective, as the spouse. I keep talking to people about vicarious trauma. I know more and have seen more than I ever want to know and ever want to see in my life because they have to have somebody to download on.

Who do they download to?

Hello, I’m it.

Don’t get cynical about hope

The words of A Veteran Family member

I didn’t really know the difference between what was normal and what wasn’t. I didn’t know what a civilian childhood looked like. I know that my childhood made me highly empathetic, and highly in tune with other people’s emotions. These things were about survival in my house. I had to be very in tune with my dad at any given second.

That was a skill I carried with me throughout my childhood. I was wiser than I should’ve been. It wasn’t until I was in university that I realized a lot of what I had been through at home came closer to abuse. It’s hard for me to say that term—abuse—because my dad never intentionally did anything. He never meant to hurt me. It just happened.

I needed to take time away from my parents to figure out what normal was supposed to look like. It became easy to say “no,” to my dad. The difficult part was acknowledging my mom’s genuinely loving requests of, “please come home,” or “your dad misses you.” That loving, non-intentional manipulation made it harder to set boundaries. I had to acknowledge that one parent is constantly doing things that are potentially abusive, but the other one is enabling those situations. I had to acknowledge that. It’s difficult to acknowledge that while so deeply, in my core, knowing how much I love my parents and how much they love me.

It’s not your job to take care of your parents. It’s their job to take care of you, and to work on their own wellness. It’s not your fault if they lash out. It’s not your fault if they don’t do things anymore—if they don’t want to get out of bed. It’s not you. It’s important to have patience with yourself, especially as a kid, and to not get too cynical about hope.

I was cynical about the idea of hope. I was depressed by the thought that hope wasn’t there. But with the right friends, the right medication, the right process…It’s hard to say it’s there, but I am saying its possible. It’s still a struggle, but there are more good day than bad days now.

150 people floating in a tin can off the coast of Libya

The words of A Royal Canadian Navy Veteran

When I was deployed to Libya, we were responsible for blockades on the water. There weren’t supposed to be any vessels coming or going. We inspected the boats in our initial phases, which meant sending personnel from our ship over to their ship to do an inspection. That’s an inherently dangerous thing. Just the physical action of going down a ladder into a small boat, onto another boat—with people who don’t necessarily want you there—is a danger.

You never knew what you’re getting yourself into. When doing the inspections, we were scouring the vessel and inspecting everything. My friend opened a duffel bag with a Russian hand grenade tied with det cord to a bag of Semtex. He stuck his head right into it. I don’t think he’s ever going to forget opening that bag. I looked in and that’s 100% what it was. I told him, “That’s an IED that you just pulled the zipper back on.”

But that was when we were in theatre.

On our way to Libya, we would come across migrant boats that were in a horrendous situation. We were trying to figure out how we could help but then we were instructed that we had to leave to go do a mission. That had significant impact on people. Leaving aside your obligations for “safety of life at sea” to go do a mission isn’t a natural thing and it bothered a lot of people for a long time.

I still wonder what happened to the mothers and children on those refugee boats. The ones we were capable of helping but we had to abandon floating in the middle of the sea because we had a mission to do. And sadly, on that day, they were not our mission.

Thanks to

Abdul Mullick, Bill Irving, Brian McKenna, Bruno Paquette, Guylaine Lamoureux, Jonathan Kowenberg, Kathryn Ward, Laryssa Lamrock, Paul Morrison, Polliann Maher, Tanis Giczi, Sharp Dopler